Conserving and remounting a framed ichthyosaur for the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Cambridge University (Nigel Larkin October 2015)

The specimen This small ichthyosaur skeleton is almost complete and remains in its original matrix. Historically this was embedded in plaster of paris and mortar within a wooden frame (approximate dimensions including frame 114cm long x 41cm wide x 17cm deep). Many years ago during a conservation project to investigate cracking on the front of the specimen the front surface was faced with foil, fibreglass and resin and the whole specimen was turned upside-down so that the front of the specimen, the skeleton itself, was underneath. The rear backing boards were taken off and most of the plaster and mortar was removed from the rear of the specimen, leaving just the pieces of matrix in place and some mortar around the edges. Some pieces of matrix and bone were disassociated and many pieces were loose. The specimen had to be re-backed and loose pieces suitably re-joined.

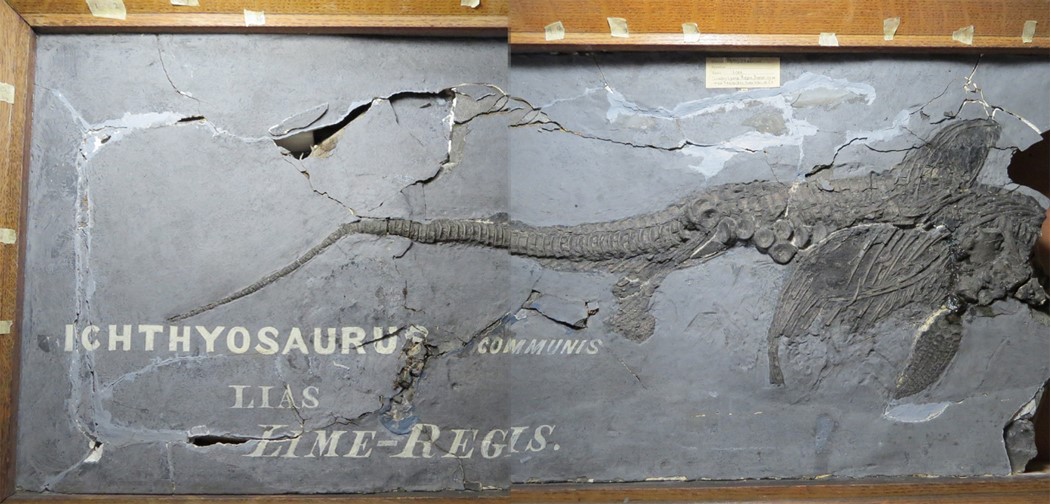

Above: The upside-down specimen with all the backing material removed (except some mortar on the right). The underlying foil can be seen in the skull region, to the left. This shows significant areas where there was no matrix in place.

Conservation The first job was to clean the rear of the specimen. Dust and dirt was removed with soft small brushes and a vacuum cleaner with the nozzle covered in gauze. All loose pieces of matrix and bone were kept as well as useful-looking pieces of plaster and mortar. The rear sides of all the pieces of matrix left within the frame were then given a coat of consolidant (Paraloid B72 in acetone at 10%). Once this was set a thicker layer was applied (this time Paraloid B72 at 25% in acetone), then finally a much thicker layer was applied (50% Paraloid B72 in acetone). This was not only to provide a firm surface for the backing material (plaster of paris) to adhere to, but also to act as a barrier layer between the plaster and the specimen. Plaster of paris was applied to the rear of the specimen after the consolidant had fully set, filling in the gaps and cracks between the blocky pieces of matrix and covering their upper surfaces by a cm or so. Plaster of paris is easily removable if required in the future.

This plaster was then covered with a couple of layers of Jesmonite AC100 acrylic resin and woven fibreglass which would provide a much more rigid and secure backing to the rear of the specimen than plaster alone. It also meant that the whole wooden frame did not have to be filled-up with plaster, keeping the specimen much lighter than it would otherwise have been and therefore reducing the chances of accidents and poor handling. Although plaster and Jesmonite resin are hygroscopic materials (they will absorb moisture from the air), the specimen has already spent at least a century embedded in similar materials without experiencing moisture-related problems such as pyrite oxidation. Therefore the hygroscopic nature of these newly applied materials should not be a concern.

Above left: The rear of the matrix covered in plaster but before Jesmonite resin was applied (the skull pieces from the left end have been removed

to be cleaned and were later re-attached). Above right: cracks in the layers of the sediment.

The skull pieces were not attached to the rest of the specimen at this stage as there was not a clear point of contact.

The whole specimen had to be turned over before the skull pieces could be carefully glued back on in exactly the right position.

So, Plastazote foam and other materials were used to pack-out the spaces behind the specimen then a temporary wooden

backing board was screwed to the rear of the wooden frame and the whole specimen was carefully turned over. The front surface of the

specimen was found to be in relatively good condition. The skeleton itself was not damaged, nor the matrix.

It was only old areas of gap-filling that had deteriorated.

Above: the front side of the specimen when it was turned over.

The front side of the specimen was cleaned, loose pieces were re-adhered with Paraloid B72 and gaps were filled with plaster and sanded down. The handful of skull pieces and associated matrix were glued back into place (with Paraloid B72 adhesive) and were backed with plaster. Relevant loose pieces of old plaster were secured back in place with new plaster. Some significant gaps around the skull were filled with more plaster and sanded down.

The fibreglass and foil panel was placed back on to the front side after acid-free tissue had been placed onto the surface of the specimen to protect it.

The panel was taped in place and the specimen was carefully turned back upside down again and the temporary backing board removed.

Plaster of paris was applied to the rear of the skull and associated matrix, followed by Jesmonite AC100 acrylic resin and fibreglass so that the backing

of this area was firmly attached to the rest of the backing material and also to ensure that it adhered to the wooden frame all the way around.

As the frame is thin and old where possible it was reinforced with batons screwed to it internally to improve its strength and give

the permanent backing board something more robust to be screwed to. The permanent backing board was treated on its inward-facing side with a coat

of Dacrylate, a clear acrylic emulsion varnish to prevent volatile organic compounds being released into the space between the board

and the specimen (a standard preventive conservation treatment). The board was then screwed into place and the specimen was carefully turned over

again so that it was the right way round with the front side uppermost.

The fibreglass and resin panel was removed from the front surface for the final phase of cleaning and conservation. Many of the details of the skeleton were obscured by a thin layer of matrix and in some places old resins or glue. For it to be fully appreciated and to look as good as it can do, this surface film had to be removed. Therefore it was cleaned very gently with an airbrasive unit using a low air pressure and a very low powder setting, utilising sodium bicarbonate, the gentlest of airbrasive powders. All traces of powder were then removed with soft brushes and a vacuum cleaner before the skeleton was given a coat of thin consolidant (Paraloid B72 5% in acetone). This helped to hold some slightly loose areas in place (with a few dabs of Paraloid adhesive as well) and also restored colour to the bones.

The front side of the specimen still required further attention (see above): plaster was sanded down and the areas around it cleaned by swabbing with dilute citric acid;

the plaster was painted out to match the matrix (artists acrylic paints were used); damaged lettering of the painted labels were repaired (artists acrylic paints were used); and the wooden frame was cleaned with dilute citric acid before being polished with natural beeswax.

Below, the finished specimen.

For more details about what we can do for you, or for a quote, please

contact:

enquiries@natural-history-conservation.com

We

are members of the Institute of Conservation.