Mounting the skeleton of 'Titus' the Tyrannosaurus rex

The whole project has been written-up and published in a peer-reviewed journal. See: Larkin, N.R., Dey, S., Smith, A.S. and Evans, R. (2022). 21st Century Rex: maximising access to a privately owned Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton in the digital age. Geological Curator 11 (6):341-353.

This 10-20 percent complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton was excavated in Hell Creek, Montana, USA, by Craig Pfister in 2018. It was shipped to Nigel Larkin in the UK in 2020. It was Nigel's job to assess and conserve the bones, and merge them with a polyurethane cast of the skeleton of 'Stan', one of the most complete T. rex skeletons ever to have been found. Nigel had to arrange the real bones and the casts into an accurate life-like posture, and to create a sturdy metal armature to hold all the bones securely in place. This armature had to be made in sections so that the mounted skeleton could be dismantled, crated, loaded on to lorries, and be transported to Nottingham. Here, at Wollaton Hall, the specimen had to be carried upstairs and through narrow doorways into the room where it would be re-assembled and put on display for the next year or so.

You can read a National Geographic article about this specimen here: Titus-the-T-rex-is-coming-to-the-UK-this-summer-heres-why-that-matters3D scanning the bones:

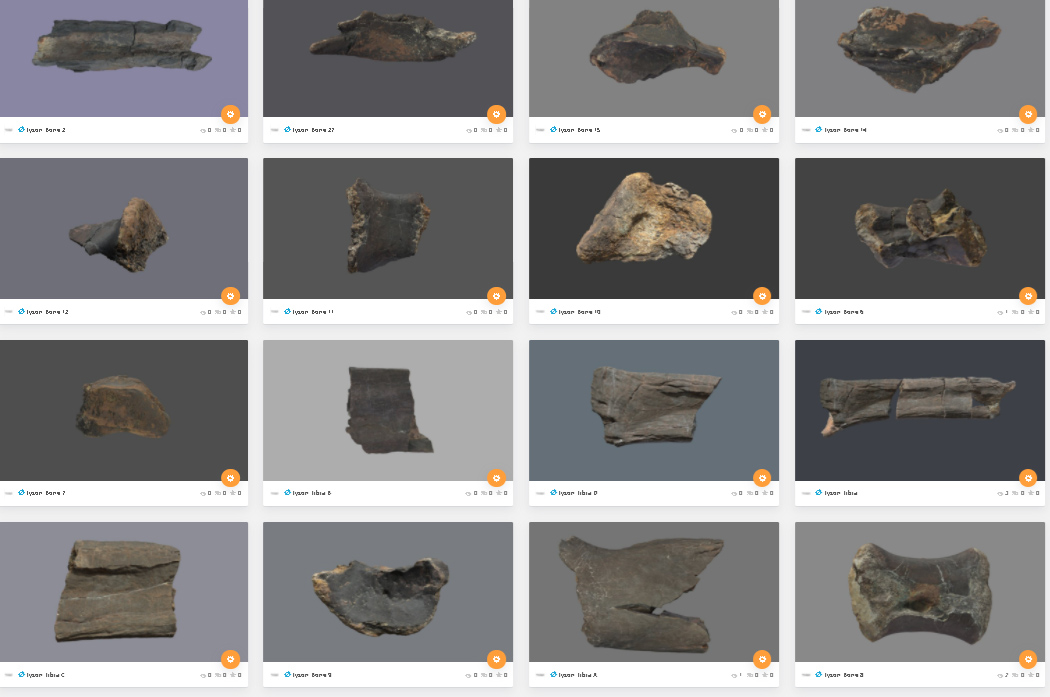

Before the mounting of the skeleton could begin, all of the real bones and bone fragments were recorded in great detail with 3D photogrammetry scanning by Steven Dey of ThinkSee3D, a specialist in 3D imaging for heritage institutions.

Detailed 3D digital models were created and shared with palaeontologists in America who were straight away able to study the bones and assess them for signs of pathology (injury and disease).

Replicas of all of these bones were 3D printed by ThinkSee3D for use in the exhibition.

Left and Middle: Steven Dey of ThinkSee3D scanning the real bones of Titus. Right: the digital 3D models online.

Mounting the bones:

The real bones of Titus were combined with the casts of bones that were replicas of the skeleton of 'Stan' (the two animals were exactly the same size in life) and a mount was made from sections of steel either welded together or bolted together as required, after being cut, heated and bent to the required shapes. Getting all the bones in their right positons relative to one another was quite a juggling act, involving webbing, ropes, pulleys and temporary supporting woodwork.

Painting the casts:

The casts of Stan were a shiny homogenous plain brown colour. They had to be scrubbed with wire brushes and acetone to remove the shine, then Gemma Larkin painted all of the casts to match the real bones of Titus.

Installation:

After a year's worth of work combining the bones, mounting them together and painting the casts, the 12m long and 4.5m high skeleton (weighing approximately 650 kg with its steel armature) was ready to be disassembled, crated, and transported to Nottingham. It took a team of people a week to rebuild the skeleton at Wollaton Hall. A plinth was constructed over the metal base, to contain 3D prints of the real bones.

A conference poster was presented on this project at the Symposium on Palaeontological Preparation and Conservation in September 2021.

Larkin, N.R., Dey, S. and Smith, A.S. 2021. 21st century Rex: Maximising access to a privately owned Tyrannosaurus rex in the digital age.

You can see this poster here: http://www.natural-history-conservation.com/TrexPoster.pdf

Below is a fun time lapse video of the installation filmed, edited and produced by the talented Dominic Day:

Acknowledgements:

With thanks to: Dr Dean Lomax and Dr Dave Hone for advice on the anatomy; Steven Dey for 3D Photogrammetry scanning; Gemma Larkin for painting the casts; Susan Jones (of Redhead Business Films) and Dominic Day for filming the project; Phil Rye for help with crating, transportation and installation; and the team at Wollaton Hall.

For more details about what we can do for you, or for a quote, please

contact:

enquiries@natural-history-conservation.com

We

are members of the United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and

Artistic Works